This talk was given by Robyn Phelan for the 2012 Australian Ceramics Triennale Conference, taking up the conference theme Subversive Clay. The following essay is the same talk, re-honed for an online readership.

Is that all there is? Should we expect more from an exhibition of ceramics than just the presentation of crafted objects? For the next 15 minutes I will be expressing observations about recent exhibitions, which have me pondering about how ceramics might be displayed to add deeper meaning and context to the work.

There is nothing like a bit humour to make one be self-reflective. This Haefeli cartoon in the New Yorker made me consider all spent hours I have spent arranging, grouping, making families, creating belongings and relationship with my ceramic vessels. Perhaps you have lost hours to this pleasure too. But this compulsion to style raises a significant question for me. When presenting work to public and our peers is the relevance of our work only about what appears carefully placed on a plinth?The balance of scale, colour, texture and all the other formal qualities of art are incredibly important for the impression of a balanced and harmonious exhibition. It is true that the culmination of our craft, is the work that we make and that this must be at the epicenter of an exhibition. But what greater reverberations of meanings and connections can a visitor take away from our exhibition? Can and should we ask of a plinth-based exhibition: Is that all there is? Haefeli’s cartoon reminded me of a particular project by our monarch of “table-scaping”.  In 2004, Gwyn Hanssen Pigott was given full access to the ceramic storage which houses the collections of Charles Freer, donated to the Smithsonian Institution in 1906. My fingers itch with desire if I imagine myself in Gwyn’s position. At the National Gallery of Victoria where I worked in collection management, the arranging of objects for permanent display is triumvirate collaboration of effort between curator, designer and installer. Gwyn alone created seven Parades for a permanent museum display freed from connection to maker, country, dynasty or technique. What inspiration might I apply to current installation practice from this project, where the maker only is responsible for its display?

In 2004, Gwyn Hanssen Pigott was given full access to the ceramic storage which houses the collections of Charles Freer, donated to the Smithsonian Institution in 1906. My fingers itch with desire if I imagine myself in Gwyn’s position. At the National Gallery of Victoria where I worked in collection management, the arranging of objects for permanent display is triumvirate collaboration of effort between curator, designer and installer. Gwyn alone created seven Parades for a permanent museum display freed from connection to maker, country, dynasty or technique. What inspiration might I apply to current installation practice from this project, where the maker only is responsible for its display?

One could apply this approach to a group exhibition where vessels are grouped by formal qualities: an idea, colour, texture or a proposition rather than by maker or making. The opportunity for collaborative curation is boundless. Gwyn’s groupings, released works from museum classification. Imagine an exhibition of new ceramic works alongside works that have inspired and influenced the maker.These muses might be the objects in your studio, gifts, childhood gismos, travel momento, fellow potters work.  Melbourne jeweller, Sally Marsland casts vessels and modifies found objects. In her exhibition, Why are you like this and not like that? Sally brings together her crafted vessels, found objects and, delightfully, the coil pot that she had made in secondary school. It was enlightening to witness a continuum of vessel form that has informed her work over many years and remains a strong continuum across a body of work.

Melbourne jeweller, Sally Marsland casts vessels and modifies found objects. In her exhibition, Why are you like this and not like that? Sally brings together her crafted vessels, found objects and, delightfully, the coil pot that she had made in secondary school. It was enlightening to witness a continuum of vessel form that has informed her work over many years and remains a strong continuum across a body of work.

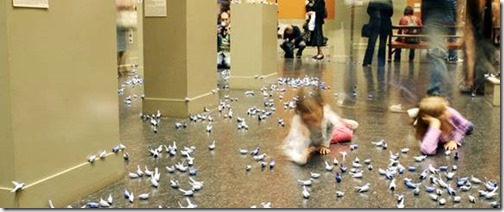

Ann Ferguson is a Victorian ceramicist who regularly works on projects with young children and is passionate about interactive experiences.

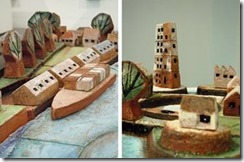

Her 2010 solo show was at Pan Gallery. Along the side of the gallery was a table of pieces to play with. For Anne, play is the important action here, making a direct connection between the artworks, how the pieces interact with each other and how this desire to touch and arrange affects the viewer. Ann was also involved with The Housing Project, a community arts event, which evolved out of community workshops and audio aural recordings from the very diverse neighbourhood of Collingwood. In this work, people are invited to create their own urban soundscape by building a city using miniature ceramic houses, trees, tall buildings and factories. These objects trigger stored sounds and voices to create a multi-layered soundscape that evolves as the pieces are moved around, on or off the platform.

Her 2010 solo show was at Pan Gallery. Along the side of the gallery was a table of pieces to play with. For Anne, play is the important action here, making a direct connection between the artworks, how the pieces interact with each other and how this desire to touch and arrange affects the viewer. Ann was also involved with The Housing Project, a community arts event, which evolved out of community workshops and audio aural recordings from the very diverse neighbourhood of Collingwood. In this work, people are invited to create their own urban soundscape by building a city using miniature ceramic houses, trees, tall buildings and factories. These objects trigger stored sounds and voices to create a multi-layered soundscape that evolves as the pieces are moved around, on or off the platform.  I pondered how this complex designed event might inform an exhibition I might do? What I take away from this show is the possibility (if your work is sturdy and you are brave) is to make an exhibition that is totally hands on where the arrangement of work is ever changing. If you are a maker of functional ware, might your exhibition only exist when it is in use and in context?

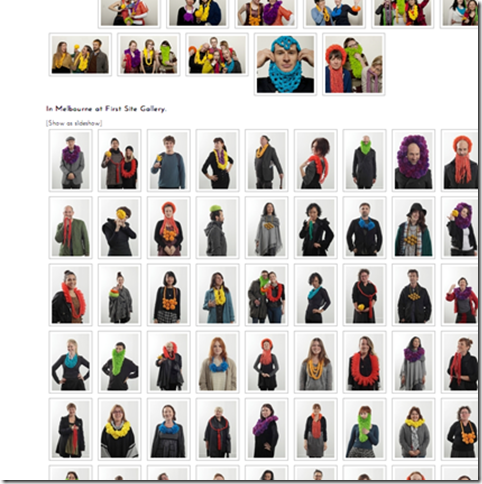

I pondered how this complex designed event might inform an exhibition I might do? What I take away from this show is the possibility (if your work is sturdy and you are brave) is to make an exhibition that is totally hands on where the arrangement of work is ever changing. If you are a maker of functional ware, might your exhibition only exist when it is in use and in context?  Claire McArdle’s is Melbourne based artist with training as a jeweller and her exhibition Public Displays of Attention, just keeps on giving. A professional photographer was employed to capture each poser. There was an incredible vibe because of the exhibition’s hands-on nature. Here Claire’s primary concern with the body, the exhibition’s title, the crafted silk pieces and the online presence combine in joyous perfection.

Claire McArdle’s is Melbourne based artist with training as a jeweller and her exhibition Public Displays of Attention, just keeps on giving. A professional photographer was employed to capture each poser. There was an incredible vibe because of the exhibition’s hands-on nature. Here Claire’s primary concern with the body, the exhibition’s title, the crafted silk pieces and the online presence combine in joyous perfection.  How a piece of jewellery engages with the human body was crucial to the Public Displays of Attention experience for Claire and her curation of the exhibition is testament to this attention. Is the feel, weight and touch vital to the experience of your pottery or ceramics? How might we be able to record the experience of holding and caressing a work made of clay without ownership as part of the exhibition experience?

How a piece of jewellery engages with the human body was crucial to the Public Displays of Attention experience for Claire and her curation of the exhibition is testament to this attention. Is the feel, weight and touch vital to the experience of your pottery or ceramics? How might we be able to record the experience of holding and caressing a work made of clay without ownership as part of the exhibition experience?

Yesterday, Clare Twomey outlined in detail her Trophy project. Her work casts a long and wonderfully challenging shadow of influence on our thinking about we can engage the visitor to our exhibitions.

In the last six months, there has been a series of exhibitions where contemporary artists have been revelling in the use of clay without particularly paying attention or having a commitment to the ceramic process. I wish to discuss some of these shows because they have forced me to consider the material qualities of clay in a different way to how I would normally engage with an exhibition by a trained ceramicist.Potters or ceramicists are part of a community of artists who have conquered the transformation of clay, so much so, that we rarely see the potential of the raw earthy stuff that is our beginnings. The flirtation with clay by Melbourne artist is a natural continuum of the last decade where contemporary artists have been using labour intensive skills or adopting the techniques of hobbyist or popular crafts.

Such terms as “hipster craft”, DIY craft come to mind. Ricky Swallow’s mount board architectural models at the 1999 Melbourne Biennial and Louise Weaver’s crochet works were some early forerunners of this approach to making.

Earlier in this conference we heard from Anton Reijnders about how people who are new to clay have a freedom of approach as they don’t know the problems of clay, are completely free and open to the material and don’t set limits to their work. Challenging for me is the low level of craft skill utilized by artists. However, what is inspiring is the honest embrace of material, technique and the desire to create a curated exhibition experience. What can I learn from these recent exhibitions?  The Figure and Ground exhibition at Utopian Slumps in April 2012, hit this trend on its earthenware head. Quote from the catalogue essay:

The Figure and Ground exhibition at Utopian Slumps in April 2012, hit this trend on its earthenware head. Quote from the catalogue essay:

The premise was to present artists who investigate the use of earthenware in contemporary art practices, particularly concerning intersections between ceramics and collage, the human figure and abstraction. The exhibition presents a curatorial interpretation of an archaeological dig by juxtaposing mounds of earth, lumps of clay and fossilised artifacts.

In response, to Sarah CrowEST and Sanne Mestrom’s work, I accepted that fired clay and found ornament could act as idea expanders, value provokers, be banal, hint at history, and force nostalgia to bubble to the surface.

Rebecca Delange’s talisman-like sculptures urged me to meditate on unfired clay as prop, glue, plinth or stuff.The next exhibition to challenge how ceramics can be presented in a gallery context, was at Craft Victoria earlier this year by Perth based potter, Jacob Ogden Smith entitled Pottery Practice Project. In Figure and Ground I relished being reminded that primary clay can be the superstar, Pottery Practice Project, Ogden Smith presents the clay process and ceramic maker as star of the show. It included video of the artist’s flicking of his long hair, attacking the surface of his freshly thrown work in a death-metal, dance-like engagement. A second video recorded his body being tattooed with a Bernard Leach kick wheel. Like a reality television show, we are never quite sure what is true motivation or construct.  Kirsten Perry’s exhibition opened yesterday (September 2012 at Lowrise Projects). It is an ode to Fleetwood Mac’s album Dreams. Here emotional attachment to naively made forms, hark back to first touches on clay that is earnest and unskilled. Perry shuns highly crafted outcomes for the sake of nostalgic effect.

Kirsten Perry’s exhibition opened yesterday (September 2012 at Lowrise Projects). It is an ode to Fleetwood Mac’s album Dreams. Here emotional attachment to naively made forms, hark back to first touches on clay that is earnest and unskilled. Perry shuns highly crafted outcomes for the sake of nostalgic effect.  And to return to whence I started, the grouping of ceramic objects. Sydney trained but Melbourne based ceramic artist Leah Jackson dreamily suspends or floats on fragile trestles, hand-pinched vessels alongside clay-made things and fragments. An Epic Romance (Craft Victoria, September 2012) consisted of four contained assemblages. Looking at each atmospheric vignette I became conscious of how my viewing of the work was being manipulated from every angle and aspect. Each still life whispered, ‘take me home I am perfectly styled and framed in every way’.

And to return to whence I started, the grouping of ceramic objects. Sydney trained but Melbourne based ceramic artist Leah Jackson dreamily suspends or floats on fragile trestles, hand-pinched vessels alongside clay-made things and fragments. An Epic Romance (Craft Victoria, September 2012) consisted of four contained assemblages. Looking at each atmospheric vignette I became conscious of how my viewing of the work was being manipulated from every angle and aspect. Each still life whispered, ‘take me home I am perfectly styled and framed in every way’.

Is this too Vogue Living? Too controlled? Honestly, I enjoyed being romanced.

Note to the reader, August 2014: The parting image presented at the Subversive Clay Conference was that of a single object on plinth. To reverse the provocation of the talk given, I reminded listeners that the eloquence of a singular statement can be striking and the language of the Modernist white cube amp; white plinth allows the viewer the space and quietude to reflect on a work. The above image is of a black glaze porcelain bowl by Prue Venables. Then director Kevin Murray, devoted the entire Craft Victoria space to this work for just one day in 2003. To ask of an exhibition, is that is there is? Sometimes it is suffice to give the answer yes.

Robyn Phelan is a Melbourne based ceramicist who graduated from RMIT in 2010. She also writes, an educator and an enthusiast about craft. Her talk reflects her professional past as a secondary visual arts teacher, her work with exhibitions and objects while working at Museum Victoria, the National Gallery of Victoria and Craft Victoria.