image

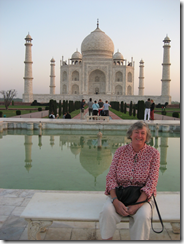

A scene from November 2005, when the rise of the stock market seemed as endless as the war on terror. |

Below is a copy of the speech I made for the opening of the graduation show of RMIT Gold & Silversmithing 2008. It was a wonderful show. Students showed how they had mastered their materials by transforming a cold material like metal into quite organic shapes and textures. It was difficult in such a celebratory atmosphere to raise the issue of our current financial crisis. But it seemed important to address this directly, in a positive way, rather than have it fester away as a silent doubt that dare not be spoken.

|

For years we have been reading predictions of a financial crisis. It wasn’t so much a question of it, but when. There was just too much leveraging going on. It would take a small shock for the market to suddenly call the bluff of derivative dealers, and the system would implode.

So while we’ve enjoyed an unprecedented period of economic growth, we have always had in the back of our minds the sense that this would come to an end. This leant an air of unreality to our prosperity—that we were living on borrowed time, as well as money.

And now that the crash has come, with prospect of a long and hard recession, we can’t help experiencing a little relief. It’s like sitting in the dentist’s chair, squirming at the pain, but inwardly knowing that at last that nagging toothache is being addressed.

While the financial situation is the ongoing story of late 2008, it has special pertinence here today, as we welcome the next generation of jewellers into the fold of Melbourne’s extraordinary jewellery culture. The last five years have seen amazing growth in the jewellery sector, with one or two new galleries opening every year. I can’t think of a city in the world with this many new jewellery galleries. And this has provided a rich field of opportunity for young jewellers, who have been extraordinarily successful in attracting the surplus capital created by an economic boom.

So what will the future hold? Jewellery is very much at the discretionary end of a personal budget. Apart from wedding and engagement rings, there is little reason other than whim to purchase an item of jewellery. We need to face the prospect that Melbourne will not have so many jewellery outlets next year, as it does today.

That’s a difficult prospect to consider right now, as we are cheering on these talented young jewellers, into a world that may not be so inclined to buy a $1,000 necklace, or $800 brooch.

But in the immortal words of Percy Bysshe Shelly, ‘If winter comes, can spring be far behind?’ While for the past few years we have been distracted by dark clouds on the horizon, now the storm is here, we can focus instead on the silver lining. As Spinoza said, ‘There is no hope without fear, and no fear without hope’.

So while cycle will eventually begin its upswing, we have possibly two or three years when things will be tight. What can be done during the lean years?

I’ve been recently fascinated by the contrast between rich and poor in Australian jewellery. This is self-evident in jewellery, with the quality of metal and stones marking a clear class distinction in their wearers. There’s an obvious contrast between the elite conceptual works made by jewellers purchased from galleries with an international reputation, and the cheap manufactured chain wear you find on the pavement in Swanston Street.

But rich and poor do not always follow a clear demographic divide. These styles quite readily flip their assigned position in society. Nothing so defines the working class as bling with bold fake stones, while versions of poverty chic are enduringly popular among the cultural elites. Ali G versus Naomi Klein.

Poor craft provides a potential rich vein of creative endeavour during a recession. And Melbourne jewellery has a strong tradition of found materials—what Penelope Pollard refers to as objets trouvé in her erudite catalogue essay.

But how will this jewellery circulate if there are fewer galleries. I think it’s interesting at this point to look across the Pacific to our cousins in Latin America, which experienced quite radical financial crisis in the early years of this millennium. In Chile’s capital, Santiago, there is a new cultural movement they called abajismo, from the word ‘abajo’ for below. This movement is led by the young people who are leaving their wealthy families in the suburbs to live close to the street in the inner city. Like Melbourne’s enchanted glade of Gertrude Street Fitzroy, a new streetwise economy has been borne.

image

By chance one evening recently I was walking down a very busy street in Santiago’s Bellavista, equivalent of Fitzroy, and stumbled across an incongruous looking vegetable garden in the middle of the sidewalk. Various greens showed signs of a loving care and there was a sign in the middle inviting neighbours to take a leaf or two, as long as they left enough for the plant to keep growing. I traced the garden to a small shopfront right opposite called Jo!, which contained a wild assortment of inexpensive jewellery made from found materials like computer keyboards. Talking with the owner, while she continued assembling these pieces on her shop counter, it seemed she had a real engagement with her neighbourhood.

That’s an enduring story of financial downturn. It brings people together. When things look good, our focus is more on individual aspirations, distinguishing ourselves from others. But during bad times, we must rely more on others.

10,000 hours is a long-term investment. You have a lifetime ahead to reap the rewards. Thankfully, these skills will be honed in the first several years after graduation. Necessity will be a faithful companion, guiding your choice of materials and design.

As the Chinese say, ’the gem cannot be polished without friction, nor man perfected without trials.’