-

Anna Davern, Absent, 2007, reworked tin placemat and biscuit tin, 250 x 200 x 5 mm, Private Collection, Photo: Terence Bogue - The book by Damian Skinner and I, Place and Adornment, was recently reviewed by Grace Cochrane for Art Jewelry Forum. Cochrane is an authoritative craft historian, and her The Crafts Movement in Australia: A History (New South Wales University Press, 1992) is a bible for researchers like myself.

While mostly positive, the review did criticise our use of the word ‘primitivism’. Here’s the relevant section from our book:

Primitivism is one of the main ways that contemporary jewellers in both Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand worked out their relationship to place, in part by making explicit references to indigenous adornment practices. This, as we will show, was less common in Australia than Aotearoa New Zealand, partly because of differences in colonial history, but it was also discarded in Australia because of the ways in which the Australian contemporary jewellers chose to position themselves in terms of place – not by embracing it, and playing up primitivism as happened in Aotearoa New Zealand, but by arguing against the relevance of place to the creative process. Interestingly, some Australasian contemporary jewellery at the beginning of the twenty-first century seems to return to primitivism, but conditionally, as if seeking to create a primitivism without reference to the ‘primitive’.

Primitivism is not the exclusive focus of our history, but it is one of the key threads we found to connect together practices in Australia and New Zealand.

Cochrane offers a concise and lucid review of primitivism in early 20th century Australasia, particularly its implication in the appropriation of indigenous cultures . This criticism helps identify a key issue in our book that warrants further elaboration.

Cochrane states:

the term “primitivism” has not been used to describe contemporary crafts (and I checked with colleagues), not because of our ignorance of the issue, but because many of the so-called “primitivist” influences are in fact continuing characteristics of cultural groups living firmly in the present, and whom we respect.

True, few jewellers used the actual term ‘primitivism’, but nonetheless their statements and creative energy reflect a desire to draw from non-Western cultures. For instance, we quote Ray Norman who critiques the intellectualist bias in Western society: “‘Our society is hung up on words, isn’t it? And all the words keep going on while other “languages” are virtually ignored.’ By contrast, the ‘aboriginal man’ still knows how to feel things intuitively.” (p.90)

The underlying assumption that can be identified as ‘primitivist’ is that the development of Western civilisation entailed an alienation from nature. This has a long legacy in Western thought, stretching at least as far back as Montaigne. His essay on Cannibals in 1577 creates this distinction between natural indigenous and corrupt European:

They are savages in the same way that we say fruits are wild, which nature produces of herself and by her ordinary course; whereas, in truth, we ought rather to call those wild whose natures we have changed by our artifice and diverted from the common order. In the former, the genuine, most useful, and natural virtues and properties are vigorous and active, which we have degenerated in the latter, and we have only adapted them to the pleasure of our corrupted palate.

This concept of the ‘noble savage’ underpinned an Enlightenment quest to think beyond existing traditions and hierarchies. While this seems bold and revolutionary in the North, where the ‘primitive’ culture exists in an exotic and distant location, it is a different story in the South, where those assigned this role actually live.

The situation in countries like the Australia and New Zealand is different. Here post-colonial critique involves a speaking part for these symbols of a more wholesome otherness. Now we hear the other side of the story as indigenous voices speak beyond these Western preconceptions. This argument bites particularly in Australia, with the Marcia Langton debate about the right of Aboriginal peoples to seek mining rights and aspire to the very middle class lifestyles that urban romantics see as inauthentic.

So where is the link today with the primitivism of our naive settler forbears?

-

Peter Tully Australian fetish 1977, coloured acrylic, coloured oil paint, wood (gumnuts), metal length 37.0 h cm, Crafts Board of the Australia Council Collection 1980, Courtesy of copyright owner, Merlene Gibson (sister) - In writing this book, we were wary of the lure of ‘contemporary’ as a state where past prejudices have been magically transcended. In tracing contemporary practices back to the settler experience we wanted to revalue the primitivist strategy to consider its positive creative potential. The idea of a ‘primitivism without the primitive’ involves taking on its radical energies without using indigenous cultures as an alibi to mask one’s own experience. Whitefellas should be able to seek a space beyond their inherited European perspectives that doesn’t involve ‘black face’ or other appropriations of indigenous culture. We see a version of that in Peter Tully’s ‘Australian Fetish’, which draws on a colonial concept yet identifies it with Australian popular cultures. His Urban Tribalism uses the space opened up by primitivism to represent city lifestyles, particularly in Gay and Lesbian communities.

The story we seek to tell is the transformation of primitivism from its origins in the patronising colonial mindset to the drive for jewellery to come from its place on the ‘other’ side of the world. This primitivism aligns with the critical force of modernism in contemporary jewellery, particularly in the critique of preciousness. According to this perspective, the meaning of jewellery has been corrupted by the capitalist system that reduces all value to the economic. One alternative lies in a return to the symbolic uses of adornment that preceded modernity. This is one of the unique perspectives that Australasian jewellery contributes to this global movement.

-

Alice Whish, Touch pins, 2006, 925 silver red and yellow ochre and natural resin, 22mm across and 8mm deep Photo by Orlando Luminere - The issue, then, seems one of terminology. We seek a broader definition of primitivism than that usually ascribed to exotic fascination, such as the inspiration that Picasso drew from masks of the Ivory Coast. In the case of contemporary jewellery, this reflects an interest in the pre-capitalist use of adornment, where it signified social identity rather than personal wealth. This is one of the most powerful references in the critique of preciousness. In this, the Pacific cultures provide important models for non-Indigenous Australasian jewellers. The challenge is to now go beyond appropriation behind the scenes and to engage in direct dialogue, as Alice Whish has done in her collaborations with Rose Mamuniny from Elcho Island.

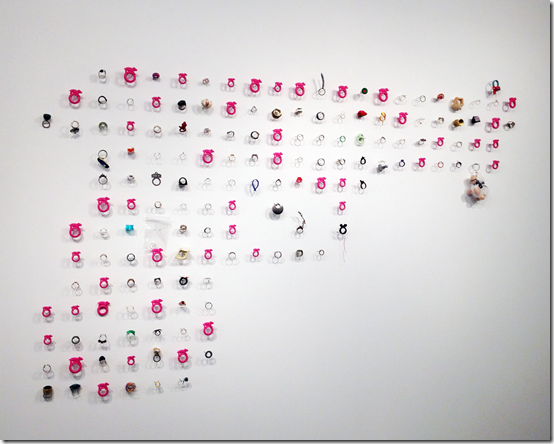

We also wanted primitivism to include non-indigenous cultures, such as the life of the street that contemporary jewellers have turned to in this century. This turn often presupposes that the energies of the street are more spontaneous and less contrived than the isolated context of the art gallery. Fashion, popular trends, tribal identities and personal narratives can be seen to give ‘life’ to jewellery, in a way parallel to the social function of adornment in traditional communities. This is a concept of primitivism that is embraced by even a resolutely modernist jeweller as Susan Cohn.

Would ‘post-primitive’ better reflect its ironic use in Australia? Maybe. But for every playful Peter Tully, there’s also a serious Ray Norman or Alice Whish. And recently, contemporary Indigenous jewellers like Areta Wilkinson and Maree Clarke seek to recover lost elements of their culture through ornament.

So maybe primitivism can be redeemed as a positive creative energy, once we stop speaking on behalf of others. As the Spanish architect Gaudi said, ‘originality consists in returning to the origin.’

Thanks for starting the argument Grace. To be continued…

Six years ago Damian Skinner approached me with the idea of a joint book about the history of contemporary jewellery in Australia and New Zealand. Damian has an impressive track record in getting books to print, and I’d always thought that the epic story of contemporary jewellery in our part of the world had yet to be fully told.

Six years ago Damian Skinner approached me with the idea of a joint book about the history of contemporary jewellery in Australia and New Zealand. Damian has an impressive track record in getting books to print, and I’d always thought that the epic story of contemporary jewellery in our part of the world had yet to be fully told.

The Australasian Craft Network has been established as a bridge down-under with the World Craft Council.

The Australasian Craft Network has been established as a bridge down-under with the World Craft Council.