After the Parallels conference at the National Gallery of Victoria, I was left thinking about the broader context for crafts in Australia. The conference was initially set up as part of the National Craft Initiative, a strategy put in place after the de-funding of Craft Australia to review what is needed by the craft sector in Australia. But naturally the event took on the interests of the host, which by charter seeks to grow its collection of unique and valuable art works.

Parallels seemed to be focused on the opportunities afforded for craft by collaborations with designers, who sell their work at international design fairs, such as Design Miami and Milan Furniture Fair. Figures like Wava Carpenter offered entre into these worlds through diverse forms of curation. The suggested strategy was to nurture these ‘facilitators’ who would help develop those international connections.

There’s no doubt that such markets help stimulate some extraordinary works, as was evident in the presentations by allied designers. Craft naturally benefits from patronage, whether it’s from monarchs, government or rich collectors. But the focus on this 1% of the 1% as direction for the Australian craft sector did seem rather narrow.

This came out in the Craft – The Australian Story symposium held the following Saturday. We heard then particularly about the other end of the spectrum – makers. Marcus Westbury, host of the ABC series Bespoke, talked about a continuum between the maker movement and studio crafts. Ramona Barry, soon to launch Craft Companion with co-author Rebecca Jobson, showed page shots that juxtaposed craft exhibition works with domestic production.

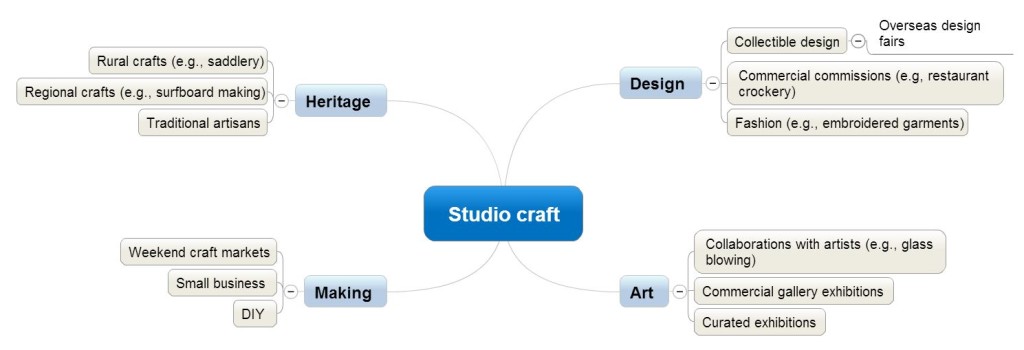

This led me to think about the different contexts in which studio craft finds itself. So I had a go at a mind map, which you can see above. I’m sure there are elements missing, don’t you think?

Studio craft is an art form that emerged post-war, along with art photography, to join the pantheon of visual arts. From the 1970s, it stood as an equal in the original Australia Council alongside visual arts, literature, music and dance. But from the 1990s it has gradually been subsumed into visual arts. Is this inevitable, or a failure of political nous?

It’s common now to hear the statement that craft is no longer a meaningful term. ‘What matters is whether it looks good!’ ‘Aren’t we over the old art/craft debate?’

Is that it? As a rusty Marxist, I tend to see this as a symptom of a consumerist society, which has lost touch with how goods are produced. For me, craft opens up the bigger picture. We don’t just as, as we would an art object, ‘What does it mean?’ We also ask, ‘How was it made, and by whom?’ We engage with an appreciation of skill, tradition and understanding of material.

But it was clear by the end of the Saturday symposium, led by the rousing Susan Cohn, that many thought craft in Australia needed to find its voice again. While our craft organisations work tirelessly for the sector, the voice of the grass-roots needs to be heard. This is a voice that asks for respect – respect for the special contribution that craftspersons make to our broader culture.

Thanks to the NGV for allowing us to hold the symposium and listing it as part of the Parallels program. Let’s hope it’s a sign of willingness to consider craft in its broader context – not just as an exotic back story, but also as a space for popular empowerment in a post-industrial world.

Roseanne Bartley is presenting a series of three

Roseanne Bartley is presenting a series of three

![charm[14]](http://craftunbound.net/images/6140d58fdafe_E39E/charm14_thumb.jpg)