Participation and Exchange (Brisbane, 12-14 July 2013) was the 15th JMGA conference since 1980. 33 years of sustained dialogue around contemporary jewellery is a remarkable achievement for relatively small population on the other side of the world to the main centres. The relative lack of collectors compared to the USA and Europe means that artists more often fall back on ideas to support their practice.

According to organisers, the theme was chosen ‘to reflect the changing focus of contemporary practice, from sole practitioner to collective participation and crossing boundaries’. The program included a diverse sample of relational projects from Australasia and Europe.

Particularly energetic were the mobile collectives of jewellers without a dedicated workshop. This included Blacksmith Doris presented by Mary Hackett as a fiercely contested space where women could come together to learn and master blacksmithing. Not so hands on, but still productive, Christine Scott-Young described the activities of Part B that make a space for experimental public engagement outside the gallery walls.

Tricia Flanagan from Hong Kong helped place participation in the context of social practice in the visual arts. As an information platform, the focus was more on the making process than the exchange of objects. Preserved Fish linked communities that share a common involvement in the fishing industry. And broad project Peripatetic Institute for Praxiology and Anthropology (PIPA) engages in ‘conspicuous moderation’ by gathering local craft skills from bricoleurs and tinkerers. It was important to have this broader context for the discussion of participation in jewellery.

Scene from Tricia Flanagan's PIPA project, collecting craft skills

Laura Bradshaw Heap spoke about her projects involving communities of women – Bosnian survivors and Irish ‘travellers’ (Roma). Her practice involved partnering with a community for ethnographic purposes, teaching them some basic jewellery techniques in exchange for information that she could then use in her own work. It was salutary to hear about her initial offer to teach jewellery to the Irish participants was rebuffed in favour of experiences, like cooking and museum visits. This precluded the possibility of including their work in the final exhibition – an exercise of free choice rather than exclusion. True exchange is impossible to pre-determine. It would have been good to hear more about the interest that Laura Bradshaw Heap brought to the exchange, particularly as initiator. There is an implied concern for displaced women – could this be developed further so that the Irish and Bosnian participants might connect?

Image from Laura Bradshaw Heap's 'This is me' project; photo: Jennika Argent

The Australian jeweller Roseanne Bartley offered a sophisticated and critical take on participation in her Seeding the Cloud project where she takes groups in different locations through the streets gathering plastic remnants that are then made into a necklace. The results are quite a diverse mix of forms and colours, which Bartley related back to the work of David Turnbull, a sociologist of science who considers the role of craft practice in creating a social fabric. Bartley raised a critical question about the nature of the social that is implied in relational jewellery.

Given the diversity of participatory paradigms, Kirsten D’Agostino’s taxonomy of collective practices was welcome. Naturally, New Zealand figured strongly as the origin of engaging new models, such as Broach of the Month Club. But this taxonomy is relatively academic without a critical framework.

The critical context for contemporary jewellery is itself in development. As a field, it seems to reward originality that reflects new aspects of the jewellery form, whether in materials or use. If this new practice of relational jewellery were to take on the critical framework of participatory art, as outlined by Claire Bishop in her book Artificial Hells, then it is likely to be riven between the competing claims of morality and freedom. For Bishop, participator art is on the one hand about filling the gaps left by privatisation and on the other a matter of exposing contradictions in our preconceptions of community. The kind of participation implied by the conference presentations were more likely the former – to fill the gaps left over in modernity.

This leads to one of the critical questions not really addressed in the conference – what kind of community does relational jewellery seek to constitute? The democratic impulse within contemporary jewellery follows the path of political movements that seek to exchange the franchise. In this sense, participation that only involves other jewelers is relatively limited. How might participation engage people who might otherwise never meet, from different parts of the world?

We didn’t have far to look. Internationally, the JMGA conference was remarkable from the number of New Zealanders, both speaking and listening. Peter Decker’s opening keynote was book-ended by Alan Preston’s evocative account of Fingers 40 year history on the last day, joined on stage at the end by all the Kiwis to sing a traditional mia. It was a touching trans-Tasman moment to remind us how powerful this dialogue across the ditch has been.

One of the real surprises came from the other side of Australia – the Indian Ocean. Helena Bugucki told of her work premised on the fantasy of being shipwrecked near Geraldton and having to make work from what’s at hand, in dialogue with a local Aboriginal man. And to the north, Alison Stone presented a paper about her experience working with a British NGO who runs jewellery workshops in Nepal. The adventure of both projects was admirable, but they didn’t provide a critical reflection on what their own role was in this situation. The principle of reciprocity seems a critical element in participation, whether it is the Aboriginal perspective on settler jewellery or Nepalese own craft traditions.

There’s a lot more to be said about participation and exchange in jewellery. The recent interest in the ‘gift economy’ brings us back to the rituals of exchange in precious objects. There are perspectives from anthropology, sociology and more recently Actor Network Theory that offer frameworks for understanding the value of the precious object in a contemporary context.

Participation and Exchange has placed all this on the agenda, which is exactly what you expect from a JMGA conference. We now have to find a forum to work through this agenda.

And the next one? The region beyond the Tasman Sea is calling. Australia is well placed to extend this conversation into the emerging contemporary jewellery scenes in Thailand, Indonesia, China and India.

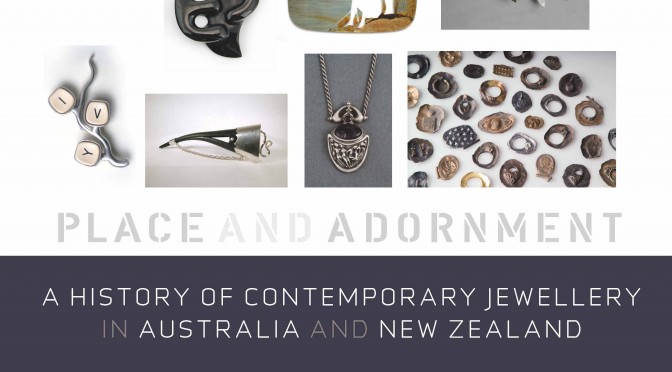

Six years ago Damian Skinner approached me with the idea of a joint book about the history of contemporary jewellery in Australia and New Zealand. Damian has an impressive track record in getting books to print, and I’d always thought that the epic story of contemporary jewellery in our part of the world had yet to be fully told.

Six years ago Damian Skinner approached me with the idea of a joint book about the history of contemporary jewellery in Australia and New Zealand. Damian has an impressive track record in getting books to print, and I’d always thought that the epic story of contemporary jewellery in our part of the world had yet to be fully told.

The new publication

The new publication