Tag Archives: collaboration

The Visible Hand: What Made in India means today

You are invited to a discussion about Australia-India partnerships in craft and design.

Thursday 21 July 6-7:30pm

Thursday 21 July 6-7:30pm

Yasuko Hiraoka Myer Room, Sidney Myer Asia Centre, University of Melbourne

Speakers include Ritu Sethi (Director, Craft Revival Trust), Chris Godsell (architect with Peddel Thorp), Sara Thorn (fashion designer) and Soumitri Varadarajan (Industrial Design, RMIT)

This is a State of Design event presented by Sangam – the Australia India Design Platform, a program of the Ethical Design Laboratory at RMIT Centre for Design, in partnership with Australia India Institute, Australia Council, City of Melbourne, Asialink and Craft Victoria.

India is both one of the world’s leading economies and a treasury of cultural traditions. While in the past, many craftspeople and artists have travelled to India for creative inspiration, today new partnerships are emerging in design. Architects, fashion designers and industrial designers are finding new opportunities in the demand for skills both inside and outside India. In particular, India has an enormous capacity of craft skill that is lacking in the West. As India gears up for increased export activity, how will the ‘Made in India’ brand compare to ‘Made in China’? What are ways of local designers to add ethical value to their products through partnership with India? How can cultural differences between Australia and India be negotiated to enable productive partnerships?

Design can play an important role in building partnerships in our region. Globalisation is now extending beyond the large-scale factories of southern China to include smaller village workshops in south Asia. This offers many opportunities for designers to create product that carries symbolic meaning. But to design product that is made in villages requires an understanding of their needs and concerns.

This event is about design practice that moves between Australia and India. It is looking at how the stories of production can travel across the supply chain from village to urban boutique.

This seminar is part of Sangam – the Australia India Design Platform, a series of forums and workshops over three years in Australia and India with the aim of creating a shared understanding for creative partnerships in product development.

RSVP by 15 July to rsvp@sangamproject.net. Inquiries info@sangamproject.net.

Sangam – the Australia India Design Platform, is managed by the Ethical Design Laboratory, a research area of RMIT Centre for Design, including researchers from Australian Catholic University, University of Melbourne and University of New South Wales. It is supported by the Australia Council as a strategic initiative of the Visual Arts Board and the Australia India Institute. Partners in Australia include Australian Craft & Design Centres including Craft Australia, Arts Law and National Association of the Visual Arts. Partners in India include Craft Revival Trust, National Institute for Design, the National Institute of Fashion Technology and Jindal Global University. This platform is associated with the World Craft Council and the ICOGRADA through Indigo, the indigenous design network.

Photo of Kolkata flower market by Sandra Bowkett

Collaboration in Experimental Design Research symposium 5-6 August

Symposium Organised by : RED Objects, Research in Experimental Design Objects, School of Design Studies, College of Fine Arts, University of New South Wales, Sydney

Call for Papers: 500 word abstract due 30 June 2011

Over the last ten years international collaboration in practice based research in design, craft, and visual art in various social contexts across the globe has accelerated, yet little focussed reflection/scholarship has emerged on the topic. As a result, theories of collaboration remain implicit, relying on tacit and indirect knowledge of the interdependencies and complexities that can arise in design collaboration. Further, studio based practitioner insights about the changing parameters influencing collaboration are elided in design scholarship. One factor that contributes to the difficulties in reflecting on collaboration is the multiple variations in which collaboration is shaped. Similarly, the ethical implications of overlooking assumptions regarding cultural conventions are rarely elaborated. This symposium maps out a broad range of perspectives on design collaboration in the global socio-economic contexts of the Asia-Pacific region, including India, Malaysia, Japan and Australia. Emerging issues of design collaboration include: design in indigenous cultures; scientific developments in design materials and process; historical design models for global collaboration; complex data visualisation in the global context; and, the social consequences of new technologies.

The RED Objects research group invites you to contribute a presentation to the two-day symposium on Collaboration.

Confirmed keynote and participants include:

- Fiona Raby, Architect, partner in Dunne and Raby; and Royal College of Art, London,

- Dr Kevin Murray, writer and curator, Australia India Design Platform.

- David Trubridge, Designer and maker of contemporary furniture, New Zealand.

- Yoshigazu Hasegawa, Green Life 21 Project, Nagoya, Japan.

Symposium Themes

— Intermixes of collaboration: the emergence of collaboration as a social phenomenon.

What implicit conventions guide collaboration between designers, artisans, artists, manufacturers, and distributors?

—Theorising the complexities of contemporary making, making and manufacturing and parameters of globalised collaboration.

What are the parameters and constraints, and opportunities and dangers for future design collaborations?

—News from the frontline: collaborative relationships between design and conventional and emerging fields.

What are the implications of recent design collaborations?

Papers presented at the symposium will be considered for electronic publication in 2011 and made available on the RED Objects website (currently under construction).

Symposium: Collaboration in Experimental Design Research

Organised by : RED Objects, Research in Experimental Design Objects, School of Design Studies, College of Fine Arts, University of New South Wales, Sydney

Dates : Friday 5 August 2011 and 10am to 5pm Saturday 6 August 2011

Times : 1pm to 8pm Friday; 10am to 5pm Saturday.

Location : COFA Lecture Theatre corner Oxford Street and Greens Road, Paddington, NSW, 2021.

For all enquiries please contact the RED Objects group via email: redobjects@cofa.unsw.edu.au or Liz Williamson on 02 9385 0627 or email: Liz.Williamson@unsw.edu.au

Australia-India Design Residency

How would you like to work with Indian craft?

Australia India Design Platform is seeking expressions of interest for an Australia-India Design Residency. AIDP is a three year program of forums and workshops in Australia and India that aims to develop fair standards in product development which can add value to craft practice in partnership with art and design.

India contains a wealth of traditional craft skills. They developed over millennia in a context of religion, caste and patronage. In the 20th century, craft became a key expression of nationalism and democracy that emerged following independence from British rule. The twin forces of globalisation and urbanisation are now threatening these crafts. Cheap imports undercut local markets and faster lifestyles provide less time for handmade production. But given the enduring importance of craft for identity, many seek to adapt craft traditions for the changing world.

Australian craftspersons and designers have been travelling to India since the 1970s. The culture is a rich source of inspiration for visitors. It not only provides a feast of colour, but also a love or adornment that can be applied to creative practice back home. In recent years, relationships have developed that represent more ongoing forms of partnership. These have included attempts at product development that provide alternative markets for otherwise languishing crafts.

These partnerships are likely to increase as artisans become more connected. But how can these kinds of craft-design collaborations develop beyond a model of outsourcing that takes production for granted? This is a time for new forms of collaboration that reflect an increasingly multilateral world and a maturing partnership between Australia and India.

The AIDP residency is an opportunity for an Australian designer or craftsperson to travel to India and develop ideas for potential product development.

Aims:

Residency details:

Residency includes:

Eligibility:

The application must contain:

Applications are due 30 June 2011 by email to aidp@newtrad.org.

For more information

This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council for the Arts, its arts funding and advisory body, and the Australia India Institute.

The Australia India Design Platform is managed by the Ethical Design Laboratory, a consortium based at RMIT Centre for Design, including researchers from Australian Catholic University and University of Melbourne. Partners in Australia include Australian Craft & Design Centres including Craft Australia, Arts Law and National Association of the Visual Arts and COFA at University NSW. Partners in India include Craft Revival Trust, National Institute for Design, the National Institute of Fashion Technology and Jindal Global University. This platform is associated with the World Craft Council and the ICOGRADA through Indigo, the indigenous design network.

Crosshatched 2011–mudka in Victoria

The focus of the Crosshatched project this year is the mudka form, the traditional Indian water storage pot, round bottomed and full bodied, as functional as it is beautiful. It is used throughout India. The ability to cool water to a pleasurable temperature due to the evaporation of water on the exterior wall of the porous body is a sustainable cooling system we could utilize in our own households.

The Crosshatched team, traditional Indian potters Manohar Lal and Dharmveer, ceramic sculptor Ann Ferguson and myself will engage with others to generate what we envisage will be an exciting 5 weeks of ceramic cross-cultural collaborations.

There are two main activities. Tallarook Stacks. A Regional Arts Victoria funded venture where by the building technique used to make mudka will be utilized to create a community sculpture. Series of these forms will be embellished with local earth materials by the Tallarook community facilitated by Ann to come together as an installation to be sited at the Tallarook Mechanics Institute.

The other, an exhibition at pan Gallery will see the mudka in its traditional form. The potters over the time they are here will make mudka, some decorated with traditional designs some unadorned. These will be woodfired in a replica of their home kilns. These will be exhibited at pan Gallery along side mudka that will have been painted by Melbourne artists. The latter will be sold via a silent auction to raise fund for improved kiln technology in their home village.

Sandra Bowkett for the Crosshatch Team

The Regional Arts Fund is an Australian Government initiative supporting the arts in regional and remote Australia, administered in Victoria by Regional Arts Victoria

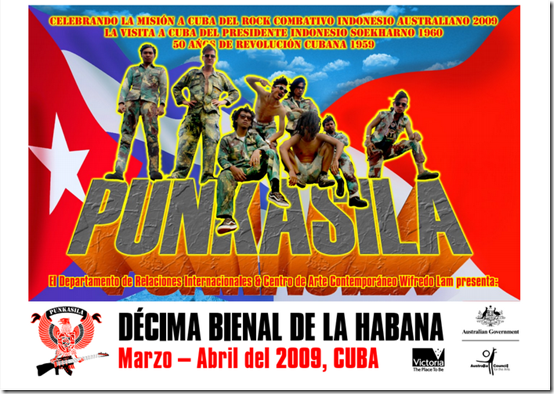

Authentic punk, handmade with attitude in Indonesia

Danius Kesminas embodies some of the wilder energies of the Australian cultural scene. The tireless Melbourne artist is very much embedded in the art world – his exhibitions in a cutting edge commercial art gallery quote from modernist art history. Yet Kesminas’ work is far from pretentious: his many projects set about attacking art’s elitism by popularising its most privileged secrets. His weapon of choice is rock music, particularly Punk. His band Histrionics perform songs about revered contemporary artists, like the Thai relational artist Rirkrit Tiravanija who transforms galleries into restaurants. The lyrics follow a familiar tune: ‘I don’t like Rirkrit, no, no / I love him, yeah /I don’t like your bean curd / Don’t mean no disrespect / I don’t like your tofu / If this dish is an art object.’

Kesminas shares a Lithuanian background with the founder of the Fluxus movement, George Maciunas. He acknowledges Fluxus in the project Vodka Sans Frontières, which traces an illegal vodka pipeline that travelled under Maciunas’ house in Vilnius. But in a different way, Kesminas’ work also seems quite at home in an egalitarian country like Australia, where the elitist authority of global visual arts has relatively little purchase.

So we might be surprised to learn that Kesminas has commissioned work from traditional Indonesian artisans. This would seem exactly like the kind of naive ‘politically correct’ art world project he would make the target of his satire. Despite its seeming worthiness, Kesminas has been able to develop an anarchic mode of collaboration which challenges our understanding of what it is to work with artisans.

At the end of 2005, Kesminas arrived in Jogjakarta for a three month Asialink residency. His only preparation for the new culture was reading a book, The Politics of Indonesia, by Damien Kingsbury. It was a dense read, filled with acronyms. Despite their inscrutability, these acronyms would later end up being an important creative resource.

Soon after he arrived, Kesminas started hanging out at the local art school. There he found a familiar scene of young rebels playing aggressive rock music. So he decided to form a band of his own and went about recruiting musicians, with immediate success. As Kesminas didn’t speak any Indonesian, they created lyrics together that were inspired by the acronyms he had read. Fortuitously, this method corresponded with a local word game plesatan, which sends up official language. For example, the song TNI is based on the acronym that stands for Tentara Nasional Indonesia (Indonesian National Military) but which is sung as Tikyan Ning Idab-Idabi (Poor but Adorable). In a similar vein, the band adopted the title Punkasila, which is drawn from the concept pancasila, the official five ideological tenets of Indonesian nationalism.

Danius Kesminas with locals celebrating the carving of the Punkasila emblem (photograph supplied by artist)

Local involvement in Punkasila expanded rapidly. A batik artist produced the band uniform in military camouflage. A wood artisan carved elaborate machine-gun electric guitars from mahogany. Others produced t-shirts, stickers, videos, etc. Much of this was well beyond Kesminas’ control, but this was exactly as he wanted it – ‘you’re a catalyst lighting this wick.’

Like many foreign artists, Kesminas enjoyed the freedom to make art in Indonesia. He contrasted this with the situation in a country like Australia where everything has to be paid for – ‘over there it’s different. You just do things because you do them.’

Given the role of the military in Indonesian life, Kesminas was afraid their provocative repertoire would endanger his collaborators. He claimed that he ‘always had to defer to them for limits. We never did anything they didn’t want to do.’ Yet at the same time, he recognised that his role as an outsider was critical: ‘There was a nice unspoken agreement. I gave them a kind of cover, as a naïve Westerner.’ It’s hard to tell who is using who in this situation. Even though punk is an identifiably Western popular movement, Kesminas associates it more broadly with a DIY principle of cultural independence. Like the paraphernalia that was locally made for Punkasila, it represents self-sufficiency in culture and defies a reliance on imported readymade products.

For Kesminas, the most significant complaint against Punkasila came from ‘NGO do-gooder missionary types’ who thought he was showing disrespect for Indonesian culture. Kesminas would claim that he actually more respectful by following the authentically carnivalesque nature of Indonesian street culture. According to this line, what we normally associate with Indonesian traditions, such as Wayang, is just a cultural commodity sustained for Western tourists. The real life is on the street.

There’s plenty to suspect Kesminas of. ‘So he likes the fact that they don’t have to be paid! But, hey, doesn’t he end up marketing their product in his exhibitions back in Australia?’ This line of interrogation seems to be missing the point, and indeed play into the very stereotype of political correctness that Kesminas’ satirises. As far as I know, the work based on Punkasila has not sold. In the meantime, Kesminas raised money for his fellow band members to participate in the Havana Biennale, which profiled them on an international stage. Sure, it all contributes to his cultural capital, but compared to other artists who use artisans like Jeff Koons, it’s relatively high on the scale of collaboration.

Indeed, there’s something quite refreshing about Punkasila. It makes us re-consider whether work with artisans must only be in forms that they are familiar with. It adds a pinch salt to our sanctimony and a dash of chili in our philanthropy.

But in the long run, there may be problems. While an important detour from cultural conservatism, we need to admit a certain guilty pleasure in Punkasila. It shows an image of Indonesian society that reflects back our familiar ideology of Western individualism. In the spirit of good ol’ rock’n roll, we have a natural tendency to champion those individuals who defy authority. We join them in solidarity against local leaders – the patriarchs, warlords and ‘tin pot dictators’.

But who are these foot solders really fighting for in the long term? We need to think of the broader context. Countries like Indonesia face significant pressures from overseas companies to ‘open up’ for ‘development’. So why should the polygamous village elder stop you from selling your land to Monsanto? Who’s the fat old chief to say you can’t sign away royalties for your village’s traditional chant? While rock’n roll is great for breaking things down, such as a military regime, it’s not disposed to building new structures.

Thank god that Kesminas has finally let the cat out of the bag. But the mice better to get organised.

Craft out of the cage – Wanda Gillespie’s marvellous discoveries

Wanda Gillespie is an Australian artist who discovered the Indonesian craft of bird cages during a residency with Asialink. While there she worked with the artisans to create a series of works based on the fictional scenario of an island that exists only in her imagination (and the now the art gallery).

This island of Swi Gunting is the scene of some remarkable discoveries. Included this very early versions of the scissor-lift (see below)…

You can find out more from her website. You can also see a short film about her stay in Indonesia and work with the artisans here. Or if you are in Melbourne, you can see it at SEVENTH Gallery, 155 Gertrude Street Fitzroy, 3-21 November.

In her invitation, she credits the work thus:

This was a collaborative project with craftsmen from Jatiwangi West Java. Project managers Anex (Nana Sukarna) and Kwa Ping Ho, and craftsmen – Didi, Tata, Ugang, Endany, Entis, Uri, Wawan, Umu. Special thanks to Jatiwangi Art Factory, Arief Yudi, Loranita Theo and Umi Luthfi.

This project was made possible with the help of Jatiwangi Arts Factory, Arts Victoria’s Cultural Exchange fund and the Anthony Ganim Postgraduate Award, (Victorian College of the Arts)

It’s another example of the very creative collaboration developing between Australian artists and Indonesian carvers. Maybe it’s time for a joint exhibition…

Horse hair – the new Chilean gold

Crin is one of Chile’s most distinctive folk crafts. In markets around the country you will find delicate forms, often taking the shape of insects, woven out of dyed horsehair. Despite its distribution around the country, almost all Crin originates from a small town called Rari.

Crin appeared mysteriously around 200 years ago, as local women found they could weave poplar roots into figures. After discovering the flexibility of horse hair they combined a Mexican plant fibre Ixtle which provided structural strength. It’s not clear why this technique emerged there in particular, but the town’s proximity to a spa resort meant that there was a ready market for cositas (little things).

Crin is made entirely by hand. No equipment is involved, even knitting needles. But unlike the chunky results of finger-knitting, crin is exquisitely fine.

As a folk craft, crin was rarely taken seriously. However, it is now finding a niche as a versatile, colourful and particularly Chilean component in the burgeoning new jewellery scene in Chile. But its recent success comes with complications.

A Santiago architect Paula Leal has been exploring ways of collaborating with artisans from Rari. An earlier attempt with weaver Alba Sepúlveda led to the award for the 2008 UNESCO Seal of Excellence for Handicraft Products. The product incorporated modernist forms of crin into a hair clasp.

But the business of incorporating crin into jewellery is actually quite a political issue. In some ways, it parallels the movement of New Zealand jewellers who sought to include local materials and techniques such as jade carving into their work. In some cases, this meant reviving some of the lost Indigenous skills, while at the same time not simply imitating traditional Maori culture.

In the case of Chile, it is still the case that you can’t incorporate crin into your work without the willing cooperation of an artisan. It seems the nature of Chilean society that local skills are not easily generalisable. It would be extremely rare for someone in Santiago to teach themselves how to weave with crin. This division of labour creates an asymmetry, particular in the relative prices of crin sold in markets and jewellery featuring crin in fashionable jewellery boutiques.

Even for someone who has achieved success such as Paula, this can be difficult. She had to find some new crin weavers when her previous collaborator broke the partnership. Apparently, she felt resentment that she was sharing the stage with a designer who didn’t actually make anything herself.

Recently, Paula Leal formed a partnership with fellow architect Manuela Tromben in the development of an exhibition devoted to crin. Orígenes Y Atuendos Imaginarios (Origins and Imaginary Outfits) included jewellery and wall work that manipulated elements of traditional crin to create new works. For instance, the cylindrical form that normally is coiled to form the body of a snail was uncoiled and introduced into a necklace form. Local jewellers Walka Studio added the silver attachments.

Crin has a long way to go. There’s potential for much experimentation. It seems inevitable that someone in Santiago will eventually learn to make it themselves. But I hope that doesn’t exclude the possibility that some of the women from Rari might themselves engage actively with product development.

But here, on the other side of the Pacific, a recent exhibition in Melbourne shows an alternative path. Vicky Shukuroglou recently completed her Masters in Gold and Silversmithing. Vicky had previously taken a South Project residency in Brazil and was interested in weaving with alternative materials. While at RMIT she had furthered her manipulation of horse hair to create extremely delicate woven structures.

![Vicky Shukuroglou object [BHH] steel wire, horse hair [double bass bow] 150 x 130 x 130mm [variable]](http://www.craftunbound.net/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2009/09/image_thumb5.png)

Vicky Shukuroglou object [BHH] steel wire, horse hair [double bass bow] 150 x 130 x 130mm [variable] |

Vicky’s objects are designed deliberately to appear insubstantial. They certainly are not made to function as jewellery, lacking solid form and metal clasps. But as such, they might seem to be true to the wispy material itself, allowing it to unravel freely. Some are likely to worry that she is taking the object out of the normal circuits of exchange that connect it with people’s lives – it can only live on a plinth. Is this a possible path in Chile?

In all, what’s happening with crin tells a story similar to other crafts across the South. Part of the post-colonial process involves coming to terms with the immediate world around us. This means not always looking North for what’s precious, but learning in how to find the beauty in what is at hand.

That process has barely begun.

![Vicky Shukuroglou object [PW] steel wire, horse hair 60 x 90mm](http://www.craftunbound.net/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2009/09/image_thumb4.png)