‘So long as beauty abides in only a few articles created by a few geniuses, the Kingdom of Beauty is nowhere near realisation.’

Bernard Leach 1

‘Fortress Ceramica’. I’m grateful to Garth Clark for so eloquently evoking the image of an institution that seems isolated from the world and resistant to the opportunities that lie in the outside work. The image of this secluded castle evokes in our minds phrases like ‘silo mentality’ that reflect old vertical hierarchies that are out of step with the flat networks of our time. For Clark, Fortress Ceramica is a bastion of the Anglo-Oriental Company, an imperial institution for the appropriation of other cultures into a self-righteous ceramic tradition. This company is besieged by the modern world, unable to adapt to the new values of our time.

The image of a beleaguered Fortress Ceramica conjures up the scene of a roundtable with knights sitting in frantic discussion as the Normans are about to scale the ramparts. What will these noble gentlemen do? Will they join the Normans, in the hope one day that they can present themselves at the glorious court of Paris? Or will they stay true to their faith, despite the great hardships they will face. We have already heard from Garth Clark of wonderful prospects for those like Grayson Perry or Jeff Koons who leave the isolation of the fortress behind for the bright lights of celebrity. Let’s look to the other path. Let’s follow one stubborn knight, Sir Bernard, who prefers to go underground for a while, in the hope that the ideals represented by Fortress Ceramica might be restored.

What are these ideals? Sir Bernard takes as his guiding principal the immortal words of John Ruskin that ‘the beauty which is indeed to be a joy for ever, must be a joy for all.’ 2 This knight’s tale considers how ceramics as a field might fare beyond its familiar craft setting, in some of the new developments in the art world.

Following the theme of medieval romance, our journey will take us to a region called ‘the green world’, 3 in reference to the forests, such as Arden and Sherwood, when heroes disappear into a mysterious other world of camaraderie and magic. In the green world, heroes leave beyond the royal power struggles for the utopian world of common folk. It is a space of transformation in narrative, appropriate to this period of change we now face in ceramics.

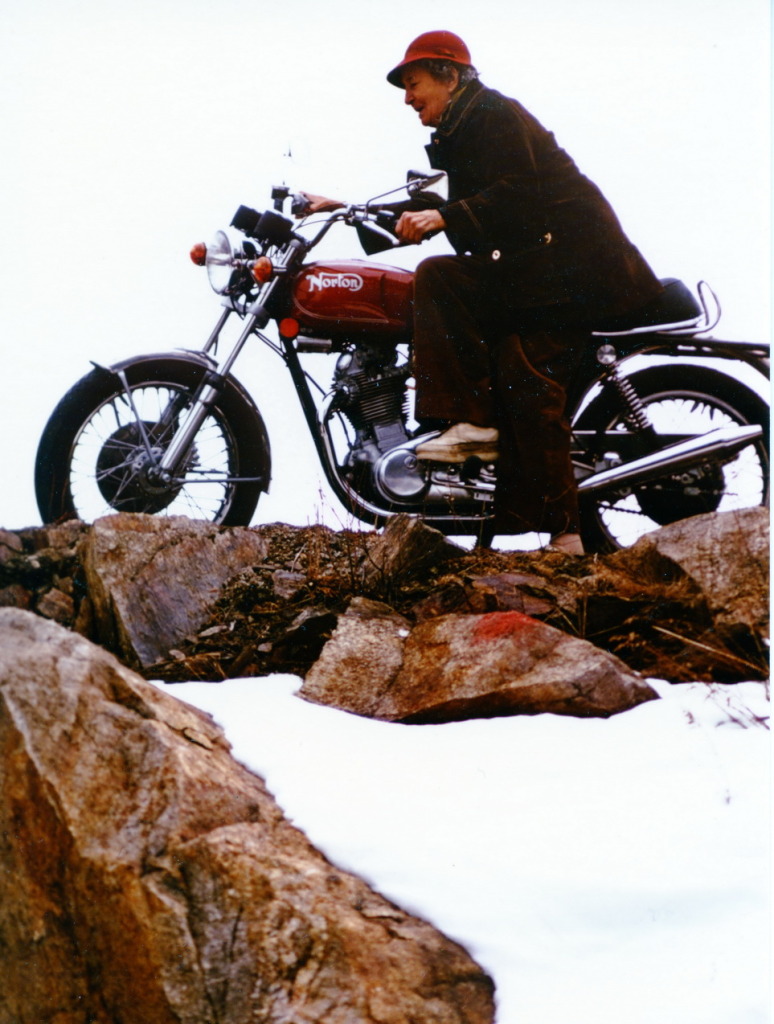

Having swam the moat and escaped the invading Normans, Sir Bernard seeks refuge in the mysterious forest. Across his path he encounters a strange object, which portends what lies ahead.

This portends strange

kmurray6d

What’s in my bag, by Kinki (2005)

It’s a handbag, or rather a handbag’s contents displayed for the entire world to see. For Sir Bernard, this is his first glimpse of life outside Fortress Ceramica. There’s a wallet, a digital camera, some tissues, candy, the inevitable iPod, keys, chewing gum, pocket PC and sundry other items. It’s hard to imagine ceramics in this sea of disposable items and gadgets. But what surprise the knight are not so much the contents themselves as that they are on public display.

This particular handbag comes from a photo-sharing site, Flickr. ‘What’s in my bag’ is a common theme for users of Flickr. This is a rather modest example of the great ‘opening out’ of inner experience that seems to have occurred in our times. Through reality television programs like Big Brother and the Internet explosion of blogs, the boundaries of public and private seem to be erased. The ‘society of spectacle’ has turned endoscopic.

The ‘network age’, as some call it, reflects an increasing interconnectness between people, particularly in the affluent west. We see it in the street, with the rise of café society and the hegemony of the latte. The talking head of current affairs has been replaced by the panel format, as non-experts trade gossip and chat about recent events. A glimpse at any train or bus will find commuters busy texting and talking on their mobile phones. I link therefore I am. And to be offline is to be nowhere.

So how goes our noble knight of clay? Rather perplexed, one might say. For Sir Bernard, ceramics is a matter of individual conscience: clay speaks from the heart.4 To see ceramics as an individual pursuit best acknowledges the investment of time and labour that has gone into the development of skills, as embodied in the hands of the potter. Long hours of solitary labour are required to test the limits of the clay and experiment with glazes. The product of this quest thrives best in the gaze of the connoisseur, who holds up the vessel and appreciates its rare colour and form, and covets private ownership. Such connoisseurs would be suspicious of an artist too connected with the world, fearing the object was produced in a moment of fashion consciousness rather than solitary inspiration.

Sir Bernard steels himself before entering the forest, realising he is straying into alien territory. This apprehension is confirmed when he comes across a strange and irreverent gathering of people-a group of merry men, no less.

Art for everyone

In visual arts, the paradigm that many have adopted to respond to the convergences of our time is relational aesthetics. Defined in the writings of Nicholas Bourriaud, relational aesthetics moves the focus in art from the lone object to the relations between people that art is seen to enable. This art creates fluid communities, which assert democratic values in resistance to the consumerism that hijacks social relations for brand identification and market penetration. As Bourriaud defines it, ‘ relational art [is] an art taking as its theoretical horizon the realm of human interactions and its social context, rather than the assertion of an independent and private symbolic space).’ 7 Here is art for the age of the mobile phone and service economy.

To the conventional gaze, relational art hardly seems like art at all. For instance, for a work in the 1996 Sydney Biennale, the artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres filled a gallery with candies wrapped in gold cellophane. Visitors were free to help themselves to this bounty. The meaning of the work was not in the installation at all, but in the position that we find ourselves as a viewer when we weigh up individual desire against the collective responsibility in order to preserve an art work for public enjoyment.6 Relational art is not a mirror to life, it creates possibilities for community.

In our tale, Nicholas Bourriaud plays the role of Robin Hood, leading a creative group of artists in redistributing the spoils of artistic value from the lone studio genius to the emerging republic of ‘extras’. Both Robin Hood and Sir Bernard would seem to share a common enemy in the Normans-or global consumerism in our time. But they have radically different approaches. Bourriaud imbues relational aesthetics with a puritan disdain for art as a form of idol worship. He rails against the ‘dead object crushed by contemplation.’ It may seem there is little prospect for an object-centric art in this movement, but there are new works which honour craft in ways that do not focus on the individually made object.

In order to gather fellow travellers in his quest, Sir Bernard ventures forth, searching for a relational ceramics that champions the ideal of art for everyone.

A soft beginning

Though most relational art is performance based and ephemeral, there are some craft-based processes, such as the Buddy System by Cook Island artist Ani O’Neill. Inspired by her Raratongan grandmother, O’Neill has devised a touring art work that recruits visitors to learn crochet and make a simple flower design. The crocheted flowers are placed on the gallery walls in an ever-growing installation. At the end of the ‘exhibition’, these flowers are sent to a person nominated by the maker. Buddy System has been quite successful for O’Neill, featuring in many cultural festivals, including the first Auckland Triennial.

Textile art would seem a natural medium for gregarious uses as it lends itself to the social group. In Melbourne, we have witnessed the knitting revolution develop as younger people sought meaningful ways of coming together outside of the commodified spaces of entertainment. While commonplace as domestic craft in the previous century, such practices as crochet today are modestly effective forms of resistance to the hyper-consumerism focused on brands and technology. As the society of spectacle renders experience ever more vicarious, through obsessions such as celebrity gossip, the very involvement of visitors in the production of the work provides opportunity for a personal stand against consumption.

Might there also be merry men of clay?

The oriental path

The field of ceramics lends itself to greater specialisation than textiles and thus seems more difficult to realise as a collective endeavour. However, in the realm of sculpture, all paths lead to one man-an Englishman who has gathered an enormous crowd of followers during his pilgrimages to distant lands, Anthony Gormley.

Anthony Gormley’s Asian Field is one of the most promoted works in the current 2006 Sydney Biennale. Asian Field is part of a series of work the British sculptor produced by recruiting people from communities to produce figurines with local clays. Previous works have come from Bristol, Mexico, Brazil and Sweden.

Asian Field was produced by 347 inhabitants of the Chinese city of Xiangshan, aged between 7 and 70 years. Their brief was to produce clay figures that were the palm-sized, could stand upright, and have two holes for eyes. Gormley had planned to include 100,000 figures, but total ended up being 192,000, made over a five day period.

kmurray6h

Anthony Gormley Asian Field installation shot from Sydney Biennale Pier 2/3, photograph by Kevin Murray

Sir Bernard is deeply impressed by the expansiveness of Asian Field . As one individual, he feels the gaze of nearly half a million eyes, an experience of both omnipotence and humility. There are also subtle variations in the clay evident across the installation, as the figures reflect the different qualities of clay distributed across the land. Asian Field certainly warrants the ‘long look’.

Intrigued, our knight approaches one of these figures. When he examines it closely, he finds to his surprise a quite crudely fashioned object, nothing like what he expected from the Chinese with their venerable traditions. Why would a great artist include works that a child could have made?

For Gormley, the series has two motives. The first is to honour the primordial mission of sculpture, as witnessed in the first human interventions into landscape which lifted horizontal rocks into vertical forms, reflecting the ascent of man from a four to a two legged beast. Thus Gormley transforms the resting nature of earth into the animated works of art.

Gormley’s second interest is to reverse the power relations in traditional art. As he says, ‘I want to democratise the space of art.’ Gormley gives over the privilege of making to the people. He is no longer the sole artist who creates the work. Rather, the work is produced as many others seek to express themselves. This reversal is parallel to the physical transformation of the gallery, from the crowd visiting the unique object to the multiple objects looking at the unique visitor. For Gormley, ‘you become the subject of art’s gaze rather than the other way round.’

All seems well and good. Gormley has been careful to acknowledge each individual participant. The installation is accompanied by photographs showing the face of the Chinese makers next to an example of their work. The combination of faces and figurines betray a rough idiosyncrasy, filled with humour and hope.

Our intrepid knight of clay finds much to admire in this egalitarianism. Sir Bernard holds dear the ideal of the ‘unknown craftsman’-the natural desire to make that is best expressed in the amateur spirit. This was an ideal he shared with his oriental brothers, who gave this anonymous production a revered Zen-like status.

His curiosity piqued, the knight inquires further. What can we learn from the objects in Asian Field about the lives of their creators? How are they different from others that have been produced in alternative cultures of the world? While eloquent about the vision of the artist, the objects themselves are surprisingly mute about their creators.

Our bold knight delves further into the world behind Asian Field .

New Chinese empire

kmurray6i

Xiangshan factory photo by Andrea Tam

In Chinese history, Xiangshan is the revered home town of the nation’s father, Sun Yat Sen. Today, it is one of Guangdong’s ‘four little tigers’, specialising in hardware, appliances, casual wear and mahogany furniture industries. Many of us are probably wearing clothes made in Xiangshan, or use their devices in our kitchens. It’s part of the revolution in consumerism that has made inflation history and has given us all access to low-cost goods.

But as enlightened consumers, we know that this prosperity can come at a cost. In a famous case, workers in a Xiangshan factory were found working for as little as $22 a month making handbags for Wal-Mart. They were forced to hand over identity documents under pain of arrest, denied overtime pay and fined if spent too long in the bathroom.

How is Gormley’s installation situated in the context of contemporary China? There is nothing in Gormley’s work or statements that relates specifically to China. Asian Field was part of a British Council campaign called Think UK; it was first exhibited in the Imperial Palace next to Tiananmen Square. If we forget, for a moment, the boundary between the worlds of art and commerce, Gormley can be seen to be following a similar path to that other Western visitor, Rupert Murdoch. Murdoch aimed to introduce STAR TV into the Chinese market, which he considered the fastest growing into the world. As Murdoch said to the Asia Society: ‘Today, hundreds of millions of Chinese not only dare to dream but have confidence that their dreams will become reality.’

Like Murdoch, Gormley is presenting China as a sea of individuals, each with their own unique aspirations. But alas, there is nothing in what they produce that connects with the traditions that inform Chinese history, from the ceramics of the Ming Dynasty to the communist ideologies of the post-imperial era. These are placeless Chinese, ready to enlist in the Hollywood dreams of Foxtel.

There’s nothing new in this. The West’s great hunger for Chinese goods has always faced the difficulty of finding something to offer in exchange. In response to the British attempt to trade for tea and porcelain, Emperor Qianlong famously pronounced to King George III, ‘We possess all things. I set no value on objects strange or ingenious, and have no use for your country’s manufactures.’ In response, the British cultivated a Chinese addiction to opium, which they could supply from their farms in India.

The west’s trade deficit with China is ballooning out. 7 What do we have to offer the Chinese that they can’t produce more cheaply and efficiently themselves? Not so much a thing, as a state of mind-individualism. The aspirational fantasies of western entertainment ( Titanic was one of Murdoch’s success stories in China) have the capacity to liberate the collective Juggernaught of China culture and unleash a sea of individual desires. They can become just like us.8

For Sir Bernard, the forest beyond Fortress Ceramica reveals itself as a place of mystery and disguise. While dressing himself up as Robin Hood, Anthony Gormley turns out to be a secret Norman, seeking to convert good people of honour into seekers of individual fortune. Next, our knight finds a Chinaman who comes dressed as a Norman. Is this another disguise?

A noble warrior reveals himself

So is this the end for Chinese ceramics in the west? Fortunately not. Also in the Sydney Biennale is the Chinese artist Ai Weiwei. His signature piece is Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (1995), which is a photographic documentation of the artist wilfully destroying a precious Chinese artefact. Ai Weiwei comments bluntly: ‘China is a factory of the world. So boring porcelain stay same 2,000 years: break.’ Naturally, our first response is to recoil with horror. Here is modernism at its most brutal-the destruction of tradition for sensational effect.

But in a way, there is something refreshing about this honesty. Ai Weiwei is performing openly what Gormley achieves by default. Weiwei’s recent work Ghost Valley Coming Down the Mountain (Museum für Moderne Kunst) featured 96 vases from the Yuan period reproduced from the original workshop. These filter ceramic tradition through a modernist lens, reducing the singular masterpiece into a grid of reproductions. While destroying the integrity of the original, Weiwei’s work honours ceramics tradition by disseminating it through a modern gaze. Like Asian Field , it replaces the one with the many, but it leaves the viewer with a means to connect with Chinese culture.

Tradition with a human face

In Australia, we have some notable examples of dialogue with China. Prominent recently in Australian galleries is Ah Xian, a refugee from Tiananmen Square. Recently collected by the National Gallery of Australia, Human Human is a life-sized figure finely ornamented by the traditional craftsmen at the Jingdong Cloisonné Factory in Hebei Province, east of Beijing. Its principle motif is the lotus, the traditional sign of hope on the journey to enlightenment. While incorporating a very traditional form of Chinese ornament, Ah Xian has made quite a radical shift in substituting the body for the vessel. For Ah Xian, this places the human body at the source of life, rather than nature.

Ah Xian can be compared to Gormley as someone who brings a humanism to China. But this humanism is not a force that forgets Chinese identity. For Ah Xian, this westernisation enables the tradition to flower in new and engaging ways.

Tradition with a western body

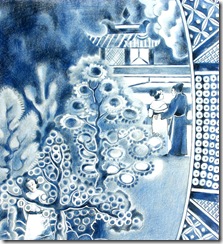

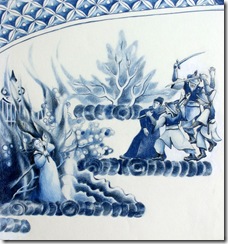

kmurray6e

Ceramic collaboration by Robin Best and Huang Xiuqian for Writing a Painting, curated by Vivonne Thwaites

Such a path is also followed by Robin Best, in work for the beautiful exhibition curated by Vivonne Thwaites, Writing a Painting , which was presented at the University of South Australia School Of Art gallery at this year’s Adelaide Festival. The exhibition featured works by Robin Best in collaboration with the Chinese ceramic painter Huang Xiuqian and the Ernabella artist Nyukala Baker.

Best’s methodology is similar to Ah Xian’s, though she herself creates the forms that are then ornamented by foreign specialist artists. Her own work is known particularly for its subtle textures that often reflect the surfaces of the landscape that inspire her. For these works, she has given the surface over as an act of collaboration.

Like Ah Xian and Ai Weiwei, Best introduces a modernist aesthetic that abstracts traditional form. But hers is a more aesthetic interest in the formal beauty of spaces created by these shapes. In flattening the traditional vase, she has heightened the painterly quality of their decoration. As cultural dialogue, it may be relatively formal, but her collaborative method does entail mutual respect.

Relational ceramics seems more a matter of collaboration than popularisation. Collaboration retains the exercise of skills which embody the traditions that individual makers represent. Popularisation seems to reduce ceramics to a clay version of ‘finger painting’ that is too crude for the expression of identity.

Collaboration, not collation

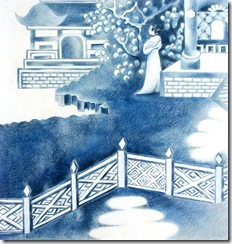

kmurray6f

Chandragupta Thenuwara and David Ray in collaboration

While there is good reason for choosing China as the partner for cultural exchange in ceramics, clay provides a language for dialogue with other countries. The Commonwealth Games project, Common Goods: Cultures Meet Through Craft , was devised to enable a reciprocal exchange between the skilled visitors from distant lands and the welcoming hosts at home. Common Goods fell under the umbrella of the South Project, which looks to possible exchanges between artists from across the south. There are many untapped connections for Australian ceramicists with the traditions of our southern cousins in Africa and Latin America. The South Project has uncovered a newly emerging field of ‘world craft’. Common Goods was just a taste of what this new genre might bring.

There were nine pairings. One of these brought together local ceramicist David Ray and Sri Lankan artist Chandragupta Thenuwara. It was an unlikely but productive partnership.

Coming from the far flung Melbourne suburb of Ringwood, David Ray has an interest in the emancipatory potential of clay. For his Open Bench residency at Craft Victoria, David created a ceramic BBQ. At the performance that culminated this, David invited audience to make pinch pots that finished the installation. While his work remained the centrepiece, the audience could experience for themselves the plasticity of the materials.

His partner Chandragupta Thenuwara has invented his own genre of art-barrelism. Barrelism is the appropriation of the military paraphernalia of Colombo as art rather than sedimented violence. The bright combination of brown, green and yellow works in Colombo to achieve precisely the opposite purpose of camouflage. This decoration enables the barrels to stand out so they prevent the flow of traffic. Thenuwara cleverly subverts this by appropriating the barrel as a work of art and celebrating it in drawing, prints, installations and ceramics.

Chandragupta took advantage of the residency with David to explore camouflage as a three-dimensional form. He hand built ceramic tiles with wave shaped protrusions in camouflage colours. In response, David pursued the militaristic theme by forming a gun made of clay, which he was able to deconstruct into building-like forms. Together with the camouflage forms, the combined work had the appearance of a city grid, resting ambivalently as war rendered into peace or the hidden violence behind prosperity.

kmurray6g

Chandragupta Thenuwara and David Ray collaborative work for Common Goods

It was a remarkable achievement given they had only three weeks, and innumerable cultural obstacles to traverse in this time. While we have had to learn to live with terror in the twenty-first century, it is a largely internalised fear. There is little evidence of threat in cities like Melbourne. The dialogue through clay with Sri Lanka offers us an opportunity to start giving form to these invisible fears.

To return to our lone craft crusader, the fall of Fortress Ceramica has not signalled the death of its ideals. There is in the area of cultural exchange a new appreciation of the capacity of clay to enable dialogue between those of different backgrounds, particularly between the consumerist west and the ‘productionist’ east. Such exchanges need to be reciprocal in order to sustain these differences while maintaining mutual understanding.

But cultural exchange is not the only adventure awaiting Sir Bernard in today’s forest, there are a number of other craft movements that take its egalitarian spirit out into the world. Let’s glimpse other paths leading out of the fortress.

Beyond the fortress 2 – a commoner’s tale

kmurray6b

Honor Freeman with porcelain powerpoint

Reflecting the knitting revolution in textiles, the recent genre of ‘poor craft’ is an attempt to renew the spirit of craft with the use of common materials. In ceramics, Nicole Lister has employed her skills in porcelain to ennoble the humble packaging that normally accompanies ceramics. Beyond the object, Honor Freeman places porcelain in the public domain in the production of fake power points. Poor craft is a definite guerrilla movement of the Fortress Ceramica, determined to maintain the ideals of object making in a world dominated by hyper-consumption.10

Beyond the fortress 3 – a worker’s tale

kmurray6c

Christian Capurro Another Misspent Portrait of Etienne de Silhouette

An alternative path is to focus on the way the object embodies the time spent in making it.

A work by Christian Capurro has some quite interesting relevance to ceramics. There are reports of a shortage of kaolin affecting porcelain production. One of the largest demands on kaolin is the production of glossy magazines. Capurro is one of a new generation of artists that turn labour into art. His work Another Misspent Portrait of Etienne de Silhouette commissioned a number of people to erase a page each from the male fashion magazine Vogue Hommes . They were asked to record how many hours it took to rub out the page, and what their normal hourly rate was. The work was thus calculated at $11,349.18.

While this kind of perverse conceptualism seems far from the ideals of the craft movement, it does suggest other paths for ceramicists, who might make a feature of their labour. Rather than selling a pot, one might sell the equivalent labour.11

Beyond the fortress 4 – a blogger’s tale

Finally, a new realm of underground action has developed recently in the production of blogs, daily web diaries. Blogs not only enable individuals to upload images and writing about their day’s concerns, but importantly it is a means of connecting people together based on shared interests. The blog becomes an informal project that solicits a mobile audience. The Danish ceramicist Karinne Erikson reflects not only on her challenges in the studio but also her involvement in a choir and occasional purchases. She adopts a popular method of dividing the week up into colours, so Red Friday includes images of Galerie La Fayette and an English stove. Part of new network includes Queensland ceramicist Shannon Garson, who used a bird theme for one week and encouraged visitors to submit works accordingly.

Conclusion

The attack on Fortress Ceramica symbolises the need to open up ceramics beyond interminable technical issues to external creative challenges. It offered as an alternative the rich opportunities available through the savvy commercial art world. Such opportunities often involve a disavowal of making and the celebration of cleverness. Trade in authenticity for relevance.

It is important to acknowledge that there are other paths leading out of Fortress Ceramica. While the field of relational aesthetics casts itself against craft as a process of commodification, there are strong affinities with its collective ideals. However, as a medium of skill, ceramics is more at home in reciprocal forms of collaboration rather than group work between strangers. Craft is for players, not bystanders.

Having lost the fellowship and security of the fortress, our gallant knight finds a spirit in the forest beyond that re-kindles his heartfelt beliefs. The tale is just beginning to unfold.

References

This is a version of a keynote paper delivered at the Verge:11th National Ceramics Conference in Brisbane 13 July 2006. It was written in response to the growing importance of relational aesthetics in the South Project, and the sense that contemporary craft needs to engage with this field of work if it is to sit alongside visual art. The paper is dedicated to Jane Sawyer, who first gave me a taste for clay when she generously took me on as a trial apprentice many years ago.

1. Bernard Leach, quoting Soetsu Yanagi, leader of Japanese craft movement, in A Potter’s Book London: Faber, 1940, p. 7

2. John Ruskin Arata Pentelici: Seven Lectures on the Elements of Sculpture London: George Allen, 1890, p. 23

3. ‘The green world has analogies, not only to the fertile world of ritual, but to the dream world that we create out of our own desires. This dream world collides with the stumbling and blinded follies of the world of experience, of Theseus’ Athens with its idiotic marriage law, of Duke Frederick and his melancholy tyranny, of Leontes and his mad jealously, of the Court Party with their plots and intrigues, and yet proves strong enough to impose the form of desire on it. Thus Shakespearean comedy illustrates, as clearly as any mythos we have, the archetypal functions of literature in visualizing the world of desire, not as an escape from ‘reality’, but as the genuine form of the world that human life tries to imitate.’

Northrop Frye Anatomy of Criticism New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1957, p. 183

4. ‘I think it is the precise quality of the machine, the nonhuman quality, that is driving hundreds of thousands of people back to clay. They want to enjoy themselves. They want to use and stretch their imaginations. They want to give expression to their feelings about life. They find clay to be a silent language, and in that language they are comparatively free to speak from the heart.’ Bernard Leach A Potter’s Challenge , p. 19

5. Nicholas Bourriaud Relational Aesthetics Paris: Les presses du réel, 2002 (orig. 1998), p. 14

6. Relational art might involve an artist cooking a dinner for a number of people. In 1993, the French artist Georgina Starr handed out sheets in a restaurant to customers dining alone, which spoke to them about the anxiety of solitary eating-anything to bring people together in unorthodox combinations.

7. ‘From virtually nothing in the 1980s, our trade deficit with China jumped to $103 billion last year. We exported just $22 billion worth of goods to China while importing $125 billion. By contrast, our trade deficit with Japan last year was 30 percent lower than that with China.’ http://www.washtimes.com/commentary/20030831-102452-7124r.htm

8. But as well as a monument to neo-colonialism, Asian Field is problematic for its message about clay. As the product of ‘unskilled’ labour, Gormley’s installation is a warning sign of the growing infantalisation of ceramics, where clay is seen as a form of spontaneous expression innocent of skill and virtuosity. A museum in Melbourne is developing a touring exhibition of ceramic horses made by children. Of course, there’s nothing wrong with that, but it would be a shame if audiences forgot the power of clay as a form of artistic expression.

9. Ceramics as a means of cementing relationships achieved its most literal expression in a recent series of events staged by Karen Casey, titled Let’s Shake . These reconciliation events involved indigenous and non-indigenous people shaking hands as the dental filling placed between the two hands slowly forms a solid impression. The clay-like substance compels two strangers to get to know each other. The length of time it takes for the material to dry dictates the duration of the relationship. The resulting negative shape of the handshake is then the material testament to the conversation. While celebrating the humanism of clay, this event highlights the seeming opposition between specialised skill and shared meaning.

10. For examples at Kevin Murray Make the Common Precious Melbourne: Craftsman House, 2005, or Craft Unbound

11. Examples of the ‘new labour movement’ were featured in an issue of Artlink in March 2005