What really is a ‘lucky country’? And how can we nurture that luck for the future?

Local inspiration has long been a focus of craft practice, and now increasingly design. The default source in many cases is landscape: often a prominent natural feature such as mountain or a unique material like mineral or flora. But landscape does not exist in itself. It is charged with the hopes and fears of the people that dwell in it.

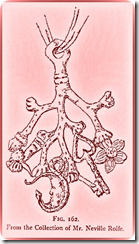

Southern Charms looks for local inspiration in the hazards that define the aspirations and fears particular to communities across the South. It aims to demonstrate how the practice of jewellery design can assist in navigating through uncertain futures.

In Chile, the predominant concern was the recurrent earthquake, which has the potential not only to destroy homes but also to break the social fabric. How to look confidently to the future when it could all collapse at any moment?

image

In Australia, there are alternative issues. The Melbourne Charm School was run as part of the State of Design Festival and was situated in

Social Studio, where recent African migrants come to learn skills in dress-making, hospitality and management. During the festival the studio demonstrated some of its re-made clothes at a fashion parade.

In the workshop, we explored the anatomy of a charm – how to design for luck. Each participant nominated a particular situation where they thought luck was badly needed.

image

Unsurprisingly, the

bushfire turned out to be a popular choice. Like the earthquake in Chile, it is a shared collective threat particular to place. While both represent inexorable forces of nature, social cohesion is vital to survival. Everyone needs to help each other to be mindful of the threat. But there are contrasts. With weather reports, we have greater warning of a potential bushfire and it affects people in the countryside more than the city, while an earthquake can happen at any time and is of greater danger to those living in crowded neighbourhoods. Still, in both cases, the local threats are as much what binds people together as local landscape, such as wattle or lapis lazuli – perhaps even more so.

It was also natural that, given the context, the plight of asylum seekers was nominated. This is a journey from a violent homeland, via ‘people smugglers’, on a leaky boat to an suspicious country. Would it be possible for Australians to send a charm to those waiting in detention camps to help them sustain hope? Could there be something that provided a token of the welcome that they might eventually receive – an object on which to pin hopes during the endless months waiting for bureaucracy to move?

But there are also many personal circumstances that require good fortune. Surprisingly, a number of nominations concerned the hazard of parents growing old. Would it be possible to design something to fill the ’empty nest’ – a sign from the departing children of gratitude for the care so far extended and best wishes for the freedom gained with less responsibilities?

Each participant made a charm specifically to assist with the issue nominated by someone else. Given the time limits, and variation in skill , there were some amazing neckpieces produced. There would need to be much more work done to ensure that the charm could ‘work’ properly, but it was a most auspicious beginning. Some examples:

![charm[14]](http://craftunbound.net/images/6140d58fdafe_E39E/charm14_thumb.jpg)

charm[14]

Certainly, there are other challenges ahead. Clearly one of the challenges that defines our global identity at the moment is climate change. Can a charm be useful in galvanising action? Maybe not. It would seem that trusting in luck to help with climate change works against an active response to the problem. Nonetheless, no one knows exactly how the earth’s weather will be affected by high concentrations of carbon. The risk of catastrophe is large enough to warrant a radical response. An object that reminds of this predicament may well have a role to play. But what would that object be? And how would we use it? That challenge lies ahead for another charm school.

Joyaviva has recently opened at RMIT Gallery, Melbourne. So begins a journey across the Pacific, to explore how the power of jewellery might be renewed for contemporary challenges.

Joyaviva has recently opened at RMIT Gallery, Melbourne. So begins a journey across the Pacific, to explore how the power of jewellery might be renewed for contemporary challenges.

![charm[14]](http://craftunbound.net/images/6140d58fdafe_E39E/charm14_thumb.jpg)