Jugalbandi is a Hindi word for collaboration. It means literally ‘twins entwined at birth’ and is applied to an improvised form of musical collaboration, sometimes involving different Indian traditions. This type of duet emerged after Independence as way of bringing together the northern and southern halves of India. A particularly good example is a duet by singers Sreeranjini Kodampally and Gayatri Asok, combining the sinewy Carnatic style with the more rhythmical Hindustani timbre. The land masses of Australia and India were also entwined at birth, when they shared the Gondwana land mass. So you can look at this 6 by 6 exhibition as a kind of ceramic Jugalbandi across the Indian Ocean.

Jugalbandi is a Hindi word for collaboration. It means literally ‘twins entwined at birth’ and is applied to an improvised form of musical collaboration, sometimes involving different Indian traditions. This type of duet emerged after Independence as way of bringing together the northern and southern halves of India. A particularly good example is a duet by singers Sreeranjini Kodampally and Gayatri Asok, combining the sinewy Carnatic style with the more rhythmical Hindustani timbre. The land masses of Australia and India were also entwined at birth, when they shared the Gondwana land mass. So you can look at this 6 by 6 exhibition as a kind of ceramic Jugalbandi across the Indian Ocean.

Specifically, 6 by 6 is a ‘form and surface’ collaboration where one person makes the basic object which the other decorates. The understanding is that culture consists of a number of concepts that can take different forms of expression, sometimes with exhilarating effect. One of my most memorable theatre experiences was seeing the Jacobean tragedy ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore performed in modern US dress by the American Theatre Company. The austere contemporary military officer’s uniforms gave this play a sense of political power that was more monumental than in the original flamboyant 17th dress. It’s as though we only explore one dimension of our culture at home, leaving other facets to be revealed elsewhere.

‘Form and surface’ collaboration is particularly suitable for ceramics, where the process of modelling and decoration are relatively separate. Sandra Bowkett used a similar method in her Cross-Hatched project in 2009, which involved collaboration between Australian ceramicists and Indian folk artists. Vipoo Srivilasa and Pushpa Kumari developed the strategy whereby one made the form, on which the other decorated in pencil, leaving the original maker to fill in the details with cobalt oxide. While very similar, 6 by 6 adds an element of surprise, where artists work only with their received objects, unaware of their story or what others are doing. This makes it a little more like the Surrealist exercise of Exquisite Corpse.

6 by 6 involves three Indian and three Australian ceramicists. Each artist makes six versions of the same form. One of each of these is then mailed to the other five who decorate it in their own style. The objects chosen are redolent of meaning.

Let’s look at the offerings.

Adil Writer

Originally from Mumbai, Adil Writer now lives in Auroville, which is an experimental international community nestled in the forest of south India, now a hub for ceramics.

For his chosen object, Writer draws from his heritage as a Parsi, the ethnic group that migrated to India when Persia converted to Islam. Parsis follow the Zoroastrian faith, which is sustained by intricate rituals involving sacred objects. For 6 by 6, Writer has chosen the saes (or sace or ses), a circular rimmed metal tray that holds silver objects, which include a cone (soparo) containing sugar rocks, a rose water sprinkler (gulaban) for spreading happiness, a metallic cup (pigani) filled with vermillion powder for regeneration and the oil lamp (divo) celebrating Zoroastrian fire worship. The saes is usually a family heirloom passed down through generations in order to maintain cultural continuity. It is activated on special occasions such as the thanksgiving (jashan) when it is polished and adorned with garlands, sweets, an egg, dry fruits and nuts, betelnut leaves, rice, water, coconut, dates, spices and herbs.

As a diasporic object, the story of the saes takes the Parsi story beyond Iran. 6 by 6 continues the process of cultural dispersal to a land across the ocean.

On the other side of the process, Writer has soda/wood-fired the five works by other artists. Ironically, fires his kiln with Australian mountain ash timber which was planted around Auroville 40 years ago for reforestation. But the tree is now considered a blight and its destruction for this project is welcome.

Sharbani Das Gupta

Sharbani Das Gupta developed her skills at Golden Bridge pottery, Pondicherry (just next to Auroville), under Ray Meeker. Her work combines an interest in the formal properties of clay with its potential to provide critical commentary on the key issues of the day, such as global environment.

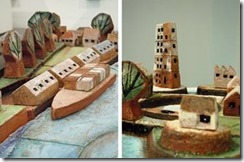

Sharbani has chosen the kaavad (‘god box’), which is a portable shrine developed in Rajasthan around 400 years ago. It became particularly important in the 17th century when the Moghul ruler Aurangzeb demolished Hindu temples and the kaavad helped maintain the sacred stories in individual homes. It is a complete wooden object with doors that unfold within doors and a drawer containing additional story scrolls. The kaavad is painted throughout with scenes from stories such as the Mahabharata, providing the bard with a device on which to base their performance. Distributed in parts to the other artists, it will only be whole again in the exhibition. Like the saes, this is a diasporic object.

In turn, Sharbani has made her received objects more useful, transforming them into a plumb line, hand warmer, magnifying tube and acupressure chart. It makes us wonder how many of our utilities began life as something more ceremonial.

Madhvi Subrahmanian

Madhvi Subrahmanian has also followed the ceramics path south-east from Mumbai to Pondicherry. Subrahmanian is particularly interested in the ancient symbolism of clay and pottery in Indian culture. Her object, the yoni, is a Hindu symbol of the divine mother, Shakti or Devi. In the temple, it is a vessel form that channels libations to the symbol of the male god, Shiva. It takes the shape of a vulva that embraces the phallic form of the lingam. On special religions festivals, or pujas, the lingam is offered libations which consist of either water from river Ganga, honey, sugarcane juice, milk, yogurt, ghee, seawater, coconut milk, fragrant oils, or rose water.

The yoni brings to 6 by 6 a particular understanding of multiplicity present in Hindu thought, especially in relation to the mystery of male and female duality within the indivisible whole. So in the logic of this collaboration, each of the artists have the opportunity themselves to offer libations in the form of pattern, glaze or smoke.

Subrahmanian’s own process involves smoke-firing, warm terra-sigillata colours derived from earth stones that are burnished and waxed. These colours are similar to those produced by Indian fabric dyes.

Gerry Wedd

Gerry Wedd from Adelaide plays with the cultural differences of West and East. He has subverted the regal language of blue and white ware to express the popular dimension of Australian culture, including surfing, football and rock music. His offering is the iconic Australian thong. The word originates from the proto-German thwang, meaning ‘to restrain’. In Australia, it took off when Dunlop released the rubber thong in 1959—a perfect fit for Australia’s informal beach culture. In summer, thongs save many Australian feet when, wet from the surf, they have to fire walk across the baking bitumen of the beach car park.

There’s an uncanny resemblance between the lingam and the thong. Both are similar shaped containers for a human appendage. But the concept of libation is a very uncommon one to such a pragmatic country as Australia, which does not usually subscribe to sacrifice as a cultural practice.

Wedd’s responses are related to the Logic Magic Kingdoms by Eduardo Paolozzi, which combined his own sculptures with several hundred museum artefacts. Such ‘collaboration’ confuses authorship and opens up new perspectives.

Trevor Fry

Trevor Fry is a creature of Sydney. As well as exhibiting in public galleries he is involved in Sydney’s artist run scene and has shown in the Mardi Gras festival. Fry was part of the Wild Boys collective that stages radical drag performances. His work is provocative, using coil-building to create transgressive objects with deviant sexual and scatological meanings.

Fry has tested the boundaries of this project by creating six different objects from the letters of the word ‘English’. The linguistic legacy of British colonisation is clearly one of the strongest links between Australia and India. But there is tension between the ‘Queen’s English’ that is maintained in formal education and its ‘bastardisation’ in the periphery of the empire. The YouTube series ‘How to talk Australians’—Indians trying to learn to talk ‘sheep shaggers’ for work in call centres—evokes a common distance from the language heard on the BBC. Fry subverts the capital letters with scenes of debauchery, invoking the cultural corruption that occurs on both sides of the Indian Ocean.

Fry has decorated the others with a camouflage design, which is both critical and decorative. He immerses these pieces in the contested terrain of Australian politics.

Janet deBoos

Janet deBoos is at the same time a very local artist, reflecting the natural beauty of the Brindabellas where she lies, and a potter of the world, working in other countries like China. She is an advocate of the ‘distributed studio’, involving collaboration between artists in varied times and places, drawing on their own unique specialisations. Her designs also involve a cultural patchwork, juxtaposing different designs on the one piece.

For this show, deBoos chose a form that celebrated Australia’s myth of the noble failure. The grand expanse of the Australian continent is littered with failed explorers, such as Ludwig Leichhardt, Burke and Wills and Lasseter. Sidney Nolan’s 1948 series of paintings reduced the bushranger Ned Kelly to a black mask with a letterbox opening. The view from the helmet flattens landscape, reducing the world to the horizontal. Next to India today, Ned Kelly evokes the failure by Australia to define itself as an independent republic.

One positive consequence of that failure is a cultural pluralism, which deBoos realises in the variety decals and glazes she uses on her received pieces.

Conclusion

6 by 6 demonstrates the power of clay to create a cultural alchemy. At one level, the works give new expression to another’s cultural forms. But through this most plastic medium, we are reminded how much cultures themselves are fluid, reflecting continual displacement. In the context of reincarnation, the Jugalbandi never ends. These twins keep being reborn.

Marea

Marea