As part of a larger project Crosshatched, two Melbourne ceramists, Ann Ferguson and Vipoo Srivilasa and visiting Indian artists Mr Pradyumna Kumar and Ms Pushpa Kumari took on the adventure of cross-cultural ceramic collaborations. There were challenges. In Crosshatched the pairs did not have a common language. Was there a universal creative language that would transcend these limitations and enable unique ceramic outcomes?

Following is the account by Ann Ferguson of her collaboration with Pradyumna Kumar and then, as described to me by Vipoo Srivilasa his collaboration with Pushpa Kumari.

Two weeks in the goldfields with beautiful tones, autumn prevailing, provided the connecting experiences that gave root to the idea, that later flourished in the form of The Universal Tree. We discovered common themes in our work and interests while exploring the landscape at our doorstep. The shapes and diversity of trees became a strong theme, one that had been explored in our previous work and one in which our common environmental concerns and interests could be expressed. Instrumental to this awakening was the presence of Minhazz Majumdar interpreting conversations, giving it context and telling us stories of India including that of the scarcity of wood and women carrying the loads on their heads while walking all day to find fuel for their fires. Later, in the children’s workshops at my workplace we read Pradyumna’s, ‘How The Firefly Got its Light’ I wondered at the power and depth of this work which spoke so lovingly of the relationship between people and trees and was touched deeply with its acute relevance to this time of great debate in Australia about fire, fear and trees.

In the studio at last, we rushed to make our special tree. Some brief conversations and plans had preceded, but mostly the work took place without words. Pradyumna’s remarkable craftsmanship together with my experience with large scale ceramic building techniques enabled this ambitious undertaking to move forward. The tree was designed in 4 sections, trunk, branching section, branch extensions and leaves. A double wall was designed to support the curve. Pradyumna built the exterior roots, reminiscent of the banyan tree. I worked on texturing bark surfaces using oxides, slips and sewing tools. An insect was painted on one side of each leaf. These were inspired by the insect focus from Pradyumna’s story. Birds and animals included both Indian and Australian species. A brightly coloured woodpecker, a weaver bird and nest, a sulphur crested cockatoo and a kangaroo are just some of the animals that live amongst the branches and under the canopy of The Universal Tree.

The limited time available for this project was foremost in Vipoo’s mind and so he was keen to establish a structure to enable an equitable collaborative productive process. They made the decision to work on a small scale. Initially Puspa made small ritual images for the festival of Sama Chakeva. Traditionally these unfired images were made over a 10 day period—different objects for different days of the festival.

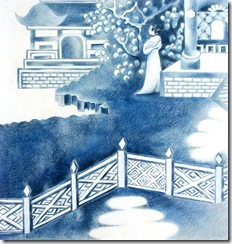

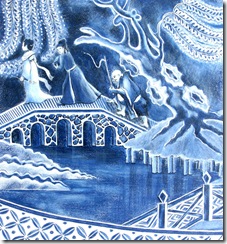

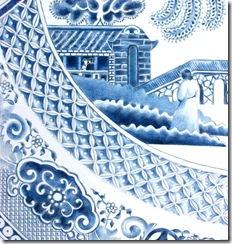

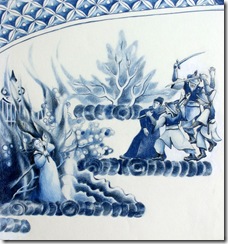

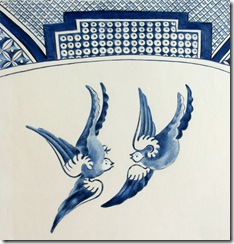

Vipoo developed a successful strategy for collaboration: one made the form, on that form the other created the decorative composition in pencil and then the other then filled in the details in cobalt oxide and then this process was reversed. Vipoo is well known for his detailed imagery, but Pushpa’s drawing skills challenged Vipoo to new levels of refinement. At times Vipoo felt frustrated by the level of communication available and thought it limited the conceptual development of the work. Pushpa had commented “You think too much”.

I asked Vipoo what was the most significant outcome for him from this collaboration and being involved with Crosshatched. He stated he was surprised with the quality of the work that was created in a short time, but appreciated the exposure to the imagery and pattern making of traditional India art. The freshness and unrestrained quality of the ‘Outsider art’ of which Minhazz had a brimming folio also captured his attention.

This report is by Sandra Bowkett. Crosshatched was organised by Sandra Bowkett and Minhazz Majumdar. For more on Crosshatched visit www.crosshatched.multiply.com. Vipoo Srivilasa is represented by Uber Gallery Melbourne. Crosshatched was financially supported by the Australia-India Council

![Vicky Shukuroglou object [PW] steel wire, horse hair 60 x 90mm](http://www.craftunbound.net/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2009/09/image_thumb4.png)

![Vicky Shukuroglou object [BHH] steel wire, horse hair [double bass bow] 150 x 130 x 130mm [variable]](http://www.craftunbound.net/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2009/09/image_thumb5.png)